I am re-reading The Blue Castle by L.M. Montgomery and decided I would write some blog posts for anyone who wants to read along with me. I originally was going to write these posts only in February, but I they will stretch into March as well now. One, I am behind on reading the book and two, that means I am behind on writing the blog posts I wanted to write for this read-along.

There will be spoilers in the chapter review posts posts so you are warned.

My plan was to password protect any of the posts with spoilers, but readers were having a hard time commenting so I removed the password protection. Scroll past them at your own risk if you have not read the book yet and want to.

If you don’t have time to read the book this month, don’t worry. These posts will be up for you to look at anytime.

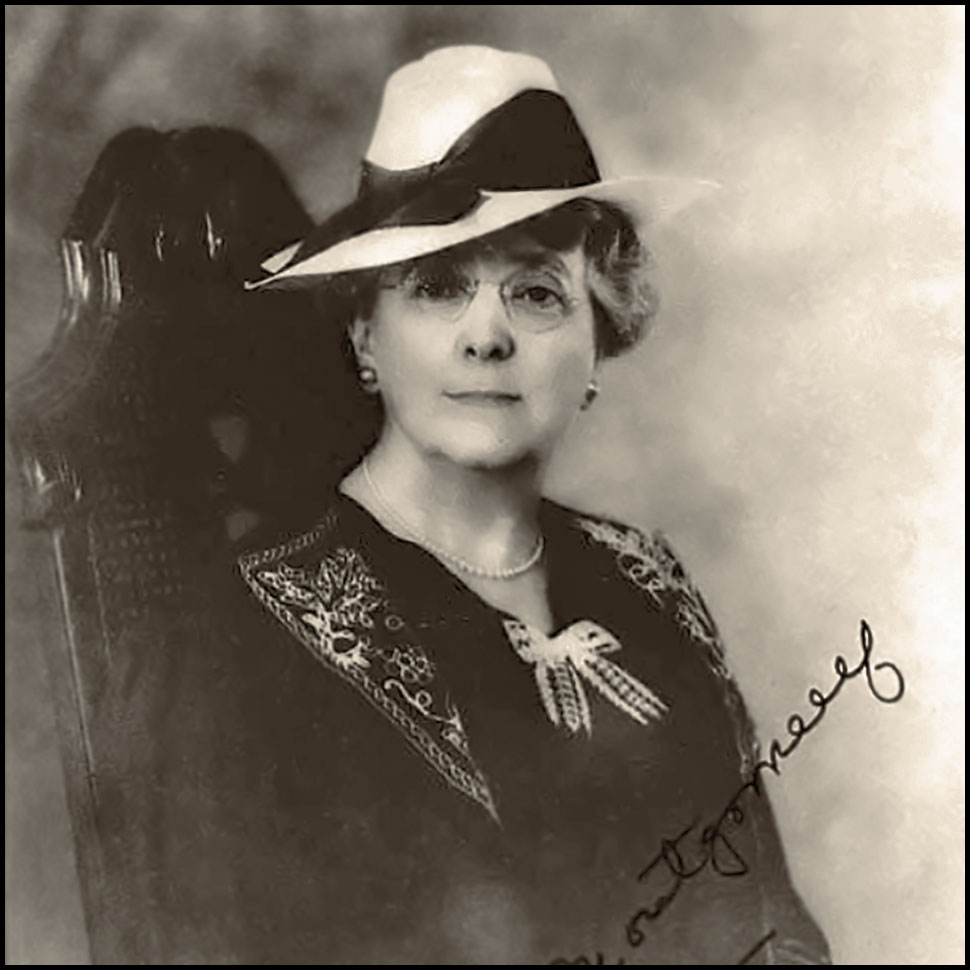

A little history of our author

For this first post, I’m going to give a little background on our author and the book.

Here is a description of the book from Goodreads for those unfamiliar with it:

An unforgettable story of courage and romance. Will Valancy Stirling ever escape her strict family and find true love?

Valancy Stirling is 29, unmarried, and has never been in love. Living with her overbearing mother and meddlesome aunt, she finds her only consolation in the “forbidden” books of John Foster and her daydreams of the Blue Castle–a place where all her dreams come true, and she can be who she truly wants to be. After getting shocking news from the doctor, she rebels against her family and discovers a surprising new world, full of love and adventures far beyond her most secret dreams.

The book is considered to be one of a few books written for adults by L.M. Montgomery, the author of Anne of Green Gables and a series of books about Anne, which are considered children’s books. They are very long children’s books, I do have to say though, and I can’t imagine today’s kids reading all of the books in the series because the ones after Anne are very wordy. Good, but wordy. And old-fashioned wordy at that too.

I am going to put a disclaimer in here for anyone who tries The Blue Castle for the first time. The first ten chapters are a bit repetitive with how depressed and oppressed our main character is. I urge you to not give up because slowly you are going to notice subtle changes in Valancy that are going to become not-so-subtle changes and eventually all-out rebellious changes that will forever change her life. In other words, the book picks up by chapter 11, and the chapters are short. Fear not!

Okay, now back to a bit of history about our author.

Many of you probably already know that L.M. stands for Lucy Maud.

Lucy Maud Montgomery was born in 1874 in New London, Canada. It was called Clifton, Canada at that time.

She had a sad beginning with her mother dying from tuberculosis when Lucy Maud was almost two. Her father left her in the care of her mother’s parents, Alexander and Lucy Maud Wooner Macneill of Cavendish and then moved to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan and remarried. He never returned for his daughter, who was called Maud after she moved in with her grandparents since her grandmother’s name was also Lucy.

Reading about her early life helped me better understand why Lucy Maud was able to write Anne Shirley’s story so well. No, Lucy Maud was not adopted in the strict sense of the word. She had parents and she lived with family after her mom passed and her father left, but an orphan spirit remained within her.

Lucy Maud was an only child living with her 50-something grandparents so her imagination, nature, books, and writing became her friends.

She started keeping a journal and writing poetry at the age of nine. She became more serious about her journal writing at the age of 14.

She completed her early education at a one-room school near her grandparents’ home, spending only one year with her father and his new wife in Prince Albert.

It was while in Prince Albert that she had her first published piece, a poem called On Cape LeForce, appear in a Prince Edward Island newspaper.

Lucy Maud eventually earned a teaching degree and taught school for three years, six months of those on Prince Edward Island, before she returned to Cavendish to care for her grandmother after her grandfather died. Sound familiar at all, Anne fans?

Lucy Maud remained with her grandmother for the next thirteen years, with the only break being a nine-month period in 1901-1902 when she worked as a proof-reader for The Daily Echo in Halifax. She wrote many of her popular works while living with her grandmother but first wrote stories or articles for various magazines and publications, working her way up until she was earning $500 a year, which was a hefty sum back then.

She wrote her first and most famous novel, Anne of Green Gables in 1905 but it was not published until 1908 due to it repeatedly being rejected by publishers who had no idea it would become such a beloved novel and, in the future, a cultural phenomenon. It would also bring a great deal of tourism to Prince Edward Island, where the book took place and where Lucy Maud lived for the first half of her life.

When her grandmother died, Lucy Maud married Rev. Ewan McDonald, who she’d actually been secretly engaged to since 1906.

I wish I could say her marriage was a good one but in truth it was not very happy and Lucy herself wrote in her journal sometime after the wedding, “When it was all over and I found myself sitting there by my husband’s side … I felt a sudden horrible onrush of rebellion and despair. I wanted to be free!”

Lucy definitely wanted to be free years later when she and her husband both struggled with their mental health. Her with depression and him with “manic-depressive insanity” (now known as bi-polar) which he was diagnosed with after World War I.

Mental illness was considered shameful at the time, so Lucy hid her and her husband’s condition. Sometimes she wrote his sermons so he could read them in church and if he was incapable of even reading them, she told everyone he’d had to go out of town..

After I found all this out, I realized one reason she wrote a book about a woman trying to break free of her mundane and difficult life after she was married was because she desperately wanted to escape her real life. She essentially said so in a 1925 journal entry.

“I have enjoyed writing it very much. It seemed a refuge from the cares and worries of my real world.” (Feb. 8, 1925)

When she finished it, she wrote, “I am sorry it is done. It has been for several months a daily escape from a world of intolerable realities.” (Mar. 10, 1925)

Marriage did bring at least something good to Lucy Maud.

Children. She had two sons (Chester Cameron in July 1912 and Ewan Stuart in October 1915 with a stillborn birth (Hugh Alexander, in August 1914 ) in between. Being a mom what she had always wanted and she wrote in her journal that motherhood “pays for all.”

She did not, however, enjoy being the wife of a minister, preferring to write in her locked front parlor, to visiting with the people of the town they moved to, pulling her from her beloved Prince Edward Island.

“To all I try to be courteously tactful and considerate, and most of them I like superficially,” she wrote in her journal, “but the gates of my soul are barred against them. They do not have the key.”

While many readers of Lucy Maud’s work would call the first Anne book (yes, there is a series of eight books featuring Anne or her family) the best she’s written, Lucy Maud herself favored Emily of New Moon because the story of a young girl trying to be a published writer when her family was so scandalized at the idea, mirrored Lucy Maud’s own life so closely.

Lucy Maud had an Aunt Emily, but she most likely based mean Aunt Elizabeth in Emily of New Moon on her Aunt Emily, many scholars say.

A cousin, the daughter of Aunt Emily, said her mother once tossed down a copy of A Tangled Web, another “adult” book by Lucy Maud, and said, “I’m ashamed to know her!”

While it’s never been made clear why Emily didn’t like her niece’s writing, some Lucy Maud scholars think it is because Emily longed to be a writer herself but couldn’t because of society’s constraints.

If you would like to read more about Lucy Maud’s life, by the way, you can pick up her memoir, The Alpine Path, which I hope to pick up someday or The Gift of Wings by Mary Henley Rubio, considered to be the definitive biography of her life. I also hope to read that one too. Much of what we know now about Lucy Maud came from her memoir and her own diaries, which Rubio used as the sources for her book.

“Forty years after Montgomery’s death, her inner life was finally revealed through her personal diaries, notebooks, scrapbooks, private correspondence and original manuscripts, all donated to the University of Guelph by her youngest son, Stuart,” Rosemary Counter wrote for Canadian Geographic in 2024. “Through them, Rubio and the close-knit community of Anne scholars would dive well beyond her books and deep into the mind of their author. For nearly a century, by design, if you knew Anne, you knew Montgomery. But all that was about to change.”

Lucy Maud suffered with anxiety at night. She often paced her floors, unclenching and clenching her hands.

She was known to take a cocktail of various drugs to help her anxiety and depression, and in 1942, after sending her manuscript, The Blythes are Quoted, off to her publisher, she took one of those cocktails, lay down, and never woke up again. She was 67.

As far as anyone in the family knew, her death was a total accident.

A couple of years ago, though, a news story came out with information from Lucy’s granddaughter, who wanted the public to know that even though the story had always been that Lucy accidentally overdosed, the family had lied out of embarrassment. There had actually been a note written by Lucy that may or may not have been a suicide note.

“May God forgive me and I hope everyone else will forgive me even if they cannot understand.”

Her son, Stuart, pocketed the note to protect her reputation, but 60-years-later Stuart’s daughter, Kate Macdonald Butler, wanted anyone suffering from mental illness to know they were not alone and could reach out for help, something Lucy Maud felt she couldn’t do.

Lucy Maud and The Blue Castle

According to Rubio, Lucy Maud was always considered a children’s book author, so when she published The Blue Castle, people were a bit thrown off.

“Its mature subject got it banned for children in a number of places” Rubio said. “While she was censored for mentioning an unwed mother (who dies, no less), young writers like [Morley] Callaghan were earning praise for sympathetic treatment of down-and-outers and prostitutes.”

Despite the backlash, The Blue Castle was a success. She wrotein her journal on Jan.22, 1927 that she received a letter from her publisher, Mr. Stokes, saying that “they have done so well with it that he wants me to write another similar to it as soon as possible.”

Some readers say A Tangled Web was that “similar book.”

Sometime in the 1990s, The Blue Castle became popular again and it has been on the reading lists of many classic book readers ever since.

If you would like to read my impressions of chapters 1 to 10 you can click this link and you will be brought to a password protected post. If you have read the book and want to discuss it with me the password is simply the word BLUE.

Sources:

https://lmmontgomery.ca/about/l-m-montgomery/

This article is fascinating:

https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/life-after-death-the-real-lucy-maud-montgomery/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/lm-montgomery-anne-green-gables-life-180981839/