They seek him here, They seek him there,

Those Frenchies seek him everywhere,

Is he in Heaven? – Is he in hell?

That demmed, elusive Pimpernel?

Last week I finished the book The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy.

I enjoyed the book so much that I looked forward to a couple chapters each night before bed just like I used to read books before there were all these devices and social media sites and everything else to distract me. Losing myself in the story completely forgetting about everything around me going on was exactly what I needed. Yes, the book could be a bit dramatic at times, but, come on, it was written in 1905!

I loved the hardcover copy I found too. It was printed about 30 years ago by Reader’s Digest but I love how it had a vintage feel to it.

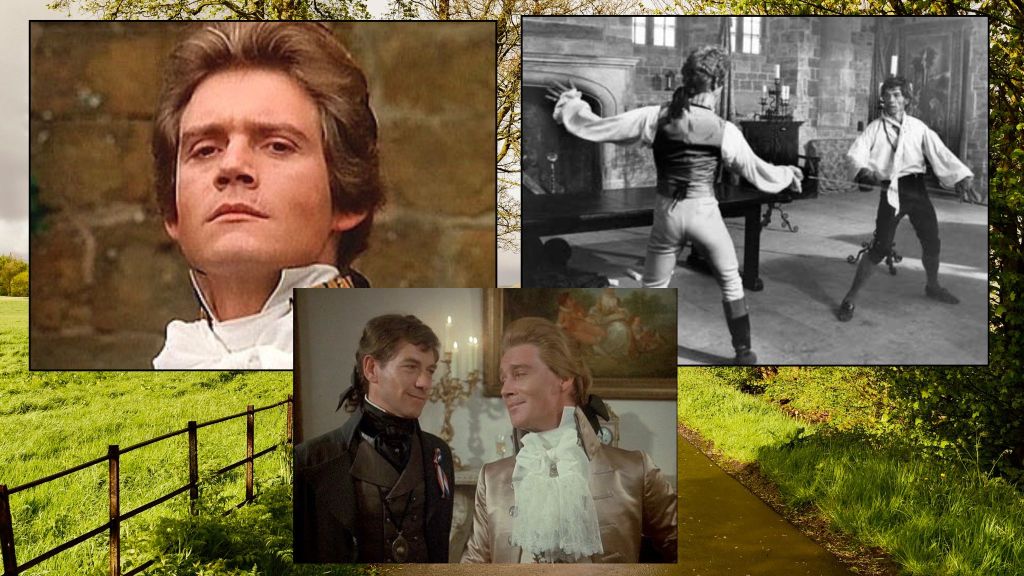

Even though I’ve seen the 1982 TV serial movie with Jane Seymour, Anthony Andrews, and Ian McKellen and therefore knew the story, I still wanted to read the book because I wanted to see if the book was different or the same.

The baroness (yes, she actually was one) wrote the play, The Scarlet Pimpernel, before she wrote the book. There are also several sequels to the book, and some don’t focus on the same characters.

First, a little description of the book and movie for those who might not be familiar with it.

Armed with only his wits and his cunning, one man recklessly defies the French revolutionaries and rescues scores of innocent men, women, and children from the deadly guillotine. His friends and foes know him only as the Scarlet Pimpernel. But the ruthless French agent Chauvelin is sworn to discover his identity and to hunt him down.

I first watched the movie version of The Scarlet Pimpernel years ago and then watched it again about a month ago. It was a CBS production with all British actors that ran three hours, maybe over a couple of nights, but I’m not sure.

After I watched the movie, I remembered I had found a hardcopy of the book by Baroness Orczy last year at a used book sale.

I couldn’t figure out how to write this without giving spoilers so … there will be spoilers. You have been warned.

First, let’s go to the book which begins with a French family being rescued from the guillotine. They’ve been brought to an inn in England by the band of men who work with The Scarlet Pimpernel. They’re exhausted but grateful. The mother in the family, referred to by the author as The Comtesse is also worried because her husband has remained in France and could be next to have his head cut off. While talking about who is who in England that she will be able to rub elbows with now that she is there, the name Lady Blakeny, formerly known as Marguerite St. Just comes up and the Comtesse balks. She doesn’t want to meet that woman because that woman turned in the Marquis de St. Cyr to the revolutionists and he and his entire family were guillotined.

The men in the inn are taken aback by this charge but don’t seem surprised the woman says it. What they are nervous about is that Lady Blakeny is currently on her way to the inn with her husband Sir Percy Blakeny, who is known as a lazy “fop”. He’s rich and simply putters his days away by hobnobbing with the Prince of Wales and other elites. He’s also terribly obnoxious. He met his wife in France and brought her back with him to live in England.

Unfortunately, the Comtesse sees Lady Blakeny and lets the woman know she wants nothing to do with her because of how she turned in the de St. Cyr family.

Lady Blakeny is confused by the charge and laughs it off.

It isn’t long before we learn that Marguerite did turn the family in but not on purpose. She dropped a hint that the Marquis was a traitor after the Marquis beat her brother Armand St. Just because he was in love with the Marquis’s daughter. She told her husband shortly after they were married and had returned to England what happened and it was after that he became very cold toward her and barely spoke to her in private, making their marriage more of a show than anything else.

The main plot of the book is a romantic one involving the misunderstandings between Marguerite and her husband.

Early on, Marguerite is approached by Citizen Chauvelin, an agent of the revolutionists in France, and he requests her to spy on those she associates with in England to see if she can find out who The Scarlet Pimpernel is.

The revolutionists want him stopped so he can no longer smuggle out aristocrats that the revolutionists want to murder.

Marguerite refuses but later in the book Chauvelin and his men find a letter that reveals her brother Armand is involved with The Scarlet Pimpernel and his men. In fact, Armand is on his way to France to set up arrangements to save another aristocrat family.

Chauvelin blackmails her, forcing her to help find out The Scarlet Pimpernel’s identity or he will have Armand killed.

She and Armand are very close because they lost their parents, and he helped to raise her so she reluctantly agrees to this plan.

Secretly Marguerite admires The Scarlet Pimpernel and his daring escapades to rescue aristocrats who are about to be killed. She harbors a ton of guilt for what happened to the Marquis and wants others to be rescued. Despite not wanting to stop The Scarlet Pimpernel, she agrees to spy in her husband’s circle of friends to see if she can learn anything about The Pimpernel’s identity, simply so Armand is not killed.

She does learn something at a future ball that the Prince of Wales is attending when she finds out that The Scarlet Pimpernel will be meeting with his men in the supper room at 1 a.m. that night. She tells Chauvelin this but when Chauvelin goes to wait all he finds is lazy, silly Sir Percy asleep on the couch.

Now in the book, Marguerite goes back to her home with Sir Percy and confronts him over how he’s been treating her. Sir Percy fights his emotions because he truly loves her despite what she did in France and believes it must have been a misunderstanding.

There is one big reason Sir Percy can’t show his love to her though. He can’t trust her and he needs to trust her because SPOILER ALERT!!!! Do not read further if you don’t want to know the truth ——

.

.

.

.

.

.

Sir Percy is actually The Scarlet Pimpernel!!! WHAT?! Now, when we watch the movie, we already know this and it makes the sexual tension even more heightened between Marguerite (Seymour) and Sir Percy (Andrews), especially after the scene where Chauvelin (McKellen) thinks he’s going to find The Pimpernel but instead only finds Sir Percy.

In the movie Marguerite runs to the dining room instead of home. The room is dark and she hears someone behind her, but she doesn’t turn around. She assumes it must be The Pimpernel so she tells him that Chauvelin is after him and trying to trap him.

This warning lets Sir Percy know that Marguerite truly supports the mission of The Scarlet Pimpernel and his band and his heart begins to melt. He steps forward, almost puts his hand on her shoulder, clearly wants to kiss her neck, but he steps back again. He doesn’t tell her who he is, preferring to protect her from any interrogation from Chauvelin.

In the book, Marguerite figures out who Sir Percy is after he leaves for France and the daughter of a man who could be killed says she heard that The Scarlet Pimpernel had left that very morning to rescue her father.

I feel like the TV movie actually fleshed some things out a bit better and added another layer which would have made the book even better.

In the movie, we see more of Lady and Sir Percy’s romance and then their marriage about halfway through. The coldness comes when Sir Percy finds out her involvement in the Marquis’s murder from someone else at their wedding reception. The person tells Sir Percy that her name was on the warrant for the Marquis’s arrest, but really we viewers know that it it is the villain Chauvelin who put her name on the arrest warrant.

Another difference between the book and the movie is that in the movie there is an underlying story of the Scarlet Pimpernel and his men trying to rescue Prince Louise XVII before he is killed in the tower, which is what happened in real life. Their goal is to smuggle the prince out of France to England and keep him there until he is older and can come back to France and take over the throne again.

There is no mention of the prince in the book and that would have been a fun layer to add.

In both the book and the movie, Marguerite sets off to rescue Percy when she learns who he is. She learns who he is the same way in the book and the movie — she runs into Percy’s office and notices there are pimpernels along the molding of the room and in other places, which helps her to put the pieces together. In the movie, though, Sir Percy leaves a note for her in his office/study, which indicates he hoped she’d figure it out. I didn’t get that in the book, but maybe I just missed that part.

Marguerite can’t bear the thought of Percy being captured and killed by Chauvelin. I liked that she went off to rescue him, which she sort of did in the movie but not in the same way.

In the book she was sneaking around and risking her life much more than she did in the movie.

I liked the show own in the movie, which didn’t happen in the book. In the book Sir Percy uses the many disguises he used to help smuggle aristocrats out to disguise himself and keep him from being discovered by Chauvelin. He disguises himself as a Jew, which seems to be a popular thing for the English to do back then. Jews were always looked down on as disgusting and dirty at that time so they were easily overlooked.

Disguised as a Jew, Percy tells Chauvelin he saw the man that might be the Scarlet Pimpernel and leads him on a wild goose chase so that his men have enough time to escae to Sir Percy’s ship.

Chauvelin believes The Scarlet Pimpernel is leaving on his ship so he leaves a bruised and beat up Marguerite behind with the bruised and beat up Jew. Of course, Sir Percy reveals himself to Marguerite once Chauvelin and his men are gone and they have a romantic reunion.

In the movie, Sir Percy is captured when Armand goes back to his lover to rescue her. In the book Armand didn’t have a lover to go back to. Chauvelin says he will only release Sir Percy if he gives the prince back, so Sir Percy leads him to a castle near the ocean. By then, though, the prince has been released.

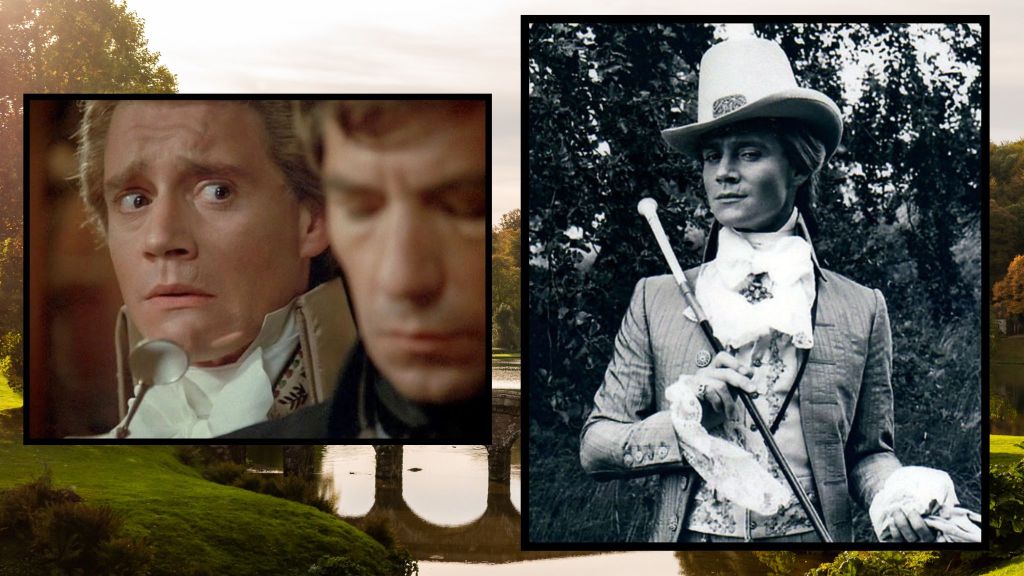

Chauvelin is pissed off and sends Sir Percy out to be shot. Unfortunately for him, Sir Percy has managed to switch Chauvelin’s men for his own and that means Sir Percy returns to the castle unscathed, has a dual with Chauvelin and wins, and then they leave Chauvelin stranded at the castle before escaping on Sir Percy’s ship to England.

The ending to the movie was a lot more exciting to me with that added dual. I’m sure it was easier to have a dual than having to explain why the French thought Jews were so gross that they would have ignored Sir Percy who was dressed up as one. Not to mention the stereotypical description of Sir Percy’s makeup, etc. would have been — well…insensitive to say the least.

The bottom line is that while I loved the book, I also loved that the movie flushed the book out even more for me.

I do hope to read the other books in the series, even if I don’t get my satisfaction of the full story of Sir Percy and Lady Blakeny.

A bit of trivia/facts about the movie taken from various sources around the web, including articles, interviews, and IMdB:

- This movie was produced by London Films and directed by Clive Donner.

- Filming took place at various eighteenth century sites in England, including Blenheim Palace, Ragley Hall, Broughton Castle, and Milton Manor; also Lindisfarne.

- The subplot with the Dauphin was taken from another one of Orczy’s novels, Eldorado, which was what the screenplay for the 1982 TV adaptation of The Scarlet Pimpernel was based on.

- Timothy Carlton, who played the Count De Beaulieu, is the father of actor Benedict Cumberbatch and ironically, McKellen would appear with Benedict in the Hobbit trilogy – or at least was in the same movies that Benedict did the voice of Smaug for. Seems Timothy felt he’d better change that last name while Benedict knew his first and last name would be an attention getter, I guess.

- Jane Seymour sometimes took her infant daughter with her to the set and had never seen the original movie from 1934 starring Leslie Howard, Merle Oberon, and Raymond Massey. (I hope to watch this in the fall or winter and compare it to the TV movie since many sources online say it is still considered the best adaptation. I saw part of it years ago, but do not remember finishing it.).

- Julian Fellowes (Prince Regent) also played the Prince Regent (the future George IV) in Sharpe’s Regiment (1996)

- London Films hoped that Andrews would one day star in a Scarlet Pimpernel series in the US, but this never occurred.

- In his 2006 work Stage Combat Resource Materials: A Selected And Annotated Bibliography, author J. Michael Kirkland referred to the sword fight between Percy and Chauvelin as “nicely staged, if somewhat repetitious … but still entertaining.” Kirkland also observed that the weapons used were in fact German sabres, which were not used during the Napoleonic era. (source Wikipedia).

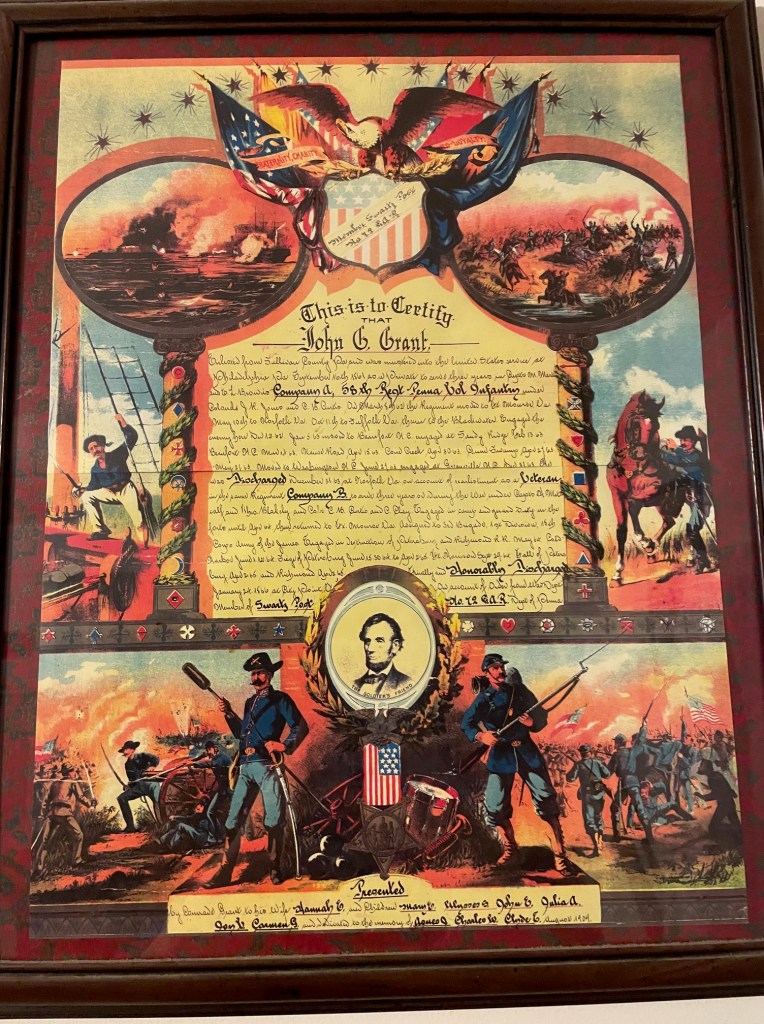

A little about the Baroness herself summarized from the back of the book:

She was born…get ready for this one! Baroness Emmuska Magdalena Rosalia Maria Josepha Barbara Orczy on Sept. 23 1865 in Tarna-Ors, Hungary. Her father was a notable composer and a nobleman and in 1868 the family was chased from Hungary during a peasant uprising, eventually settling in London when the Baroness was 15. Before that she attended schools in Paris and Brussels. She was once quoted as saying that London was her “spiritual birthplace.”

Emmuska learned to speak English quickly, fell in love with art and writing and eventually married illustrator Montaque Barstow. They had one son.

She and her husband wrote the play about Sir Percy Blakeny in 1903 based on a short story Emmuska had written. The play ran in London. Emmuska wrote the novelization and released it in 1905. The book was a huge success and she went on to write other stories about Sir Percy Blakeny and his friends, but she also wrote more plays, mystery fiction, and adventure romances.

Have you read the book and/or seen the movie of The Scarlet Pimpernel? If so, what did you think of them?

How about the Baroness’s other books – have you read any of them?

I found this movie for free on YouTube, but it is streaming on various other services, including Amazon, Sling TV, Roku, and Apple.