“I have not had a letter from you in a long time so I thought I would write to you and see if you were well and inquire as to how brother Charles is getting along. I have been uneasy for his welfare as our prisoners get very bad treatment at Belle Island and Richmond.”

Letter to William Grant from his brother John G. Grant, Washington DC, Dec. 22, 1863

When some people research the past, they find it interesting but are somewhat disconnected from what happened. They may read something sad and say, “Oh, well, how awful.” They feel down for a bit, and they move on.

When you research your family history, though — reading letters from them, getting to know them through those letters and photos of them — it all becomes a bit more personal. Suddenly you, or shall I say that “I” feel very close to the people I am reading about and about the world they lived in.

More than once I have teared up, choking back a sob, thinking of the suffering my family faced as I’ve read letters, journal entries, or biographies of their lives.

There was history all around me growing up. When I was a child there was a large, old trunk in the closet in my bedroom. I had no idea what it was and used to prop up my stuffed animals on it.

It wouldn’t be until years later I would learn the trunk belonged to my great-great grandfather, John G. Grant, a Civil War vet, and held American flags, and other memorabilia from my great-great grandparents and their family inside. After the war, John became a doctor and before that he was a letter carrier for the Union Army in Richmond after the war. I’m not sure where the bloodletting set and the letter carrying case of John’s was stored but I know they are with my dad now.

John mentioned his trunk in a letter from August 20, 1862, where he also foreshadows his interest in the medical field.

“I should like to have my chart of Frenology (sic). I think I put in my little trunk upstairs, or else it is about the house somewhere. I suppose you know what book I mean. I used to call it my Frenology book. Please get it and send it to me as soon as you get this letter.”

He was stationed at an Army training camp near Germantown, Pa. at the time.

In case you are curious, phrenology is: “the detailed study of the shape and size of the cranium as a supposed indication of character and mental abilities.”

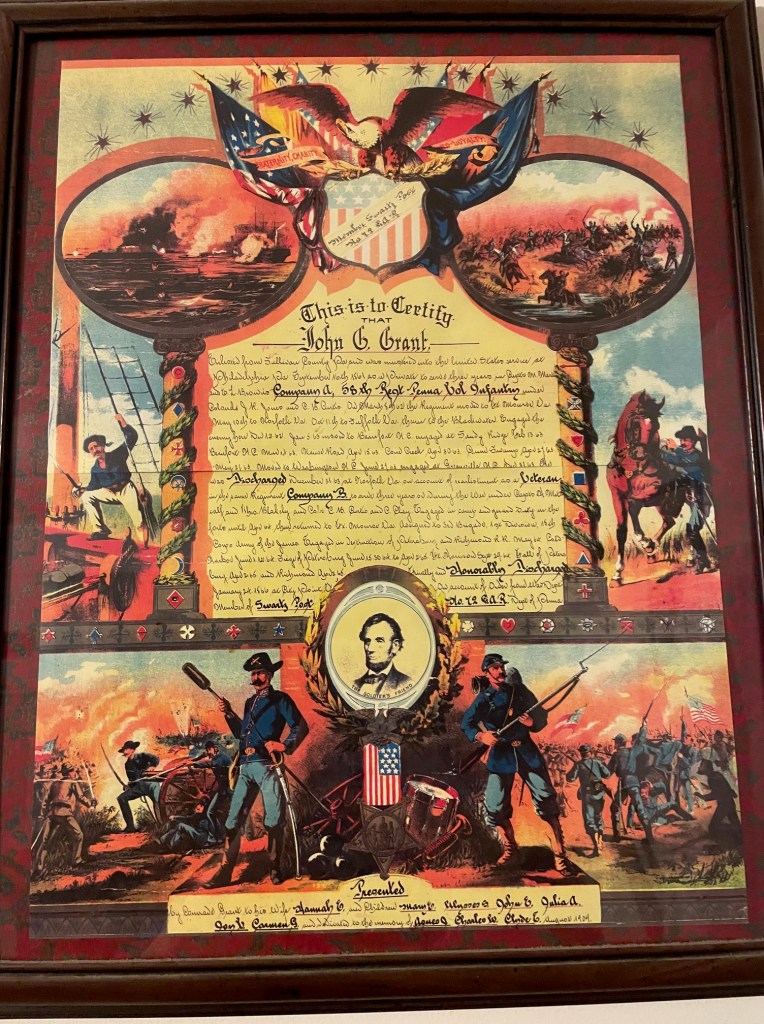

When I was in college, and after my family had moved in with my paternal grandmother, she and I were looking at historical documents and pulled out some old papers from under her bed. We found a large, original poster that appeared to show all the battles John Grant had fought in. It stated that it had been presented to his family sometime after he was discharged from the Army.

Grandma was thrilled and fascinated. Either she’d forgotten or didn’t realize the poster was there. My history-loving aunt, Eleanor, drove down from her farm in Upstate New York, took the poster and had copies made for all of my grandmother’s children, grandchildren and great grandchildren. One is hanging on my wall in our house today. I believe my dad has the original.

When I read the letters written during the Civil War between my great-great-grandfather and his half-brothers I find myself thinking of the history of this time period that I’ve read in textbooks – how it wasn’t history for them but reality.

One of the hardest realities my great-great grandfather and his half-brother, William Grant, had to face would come when they learned that their brother, Charles, had been taken prisoner by the Confederates shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg.

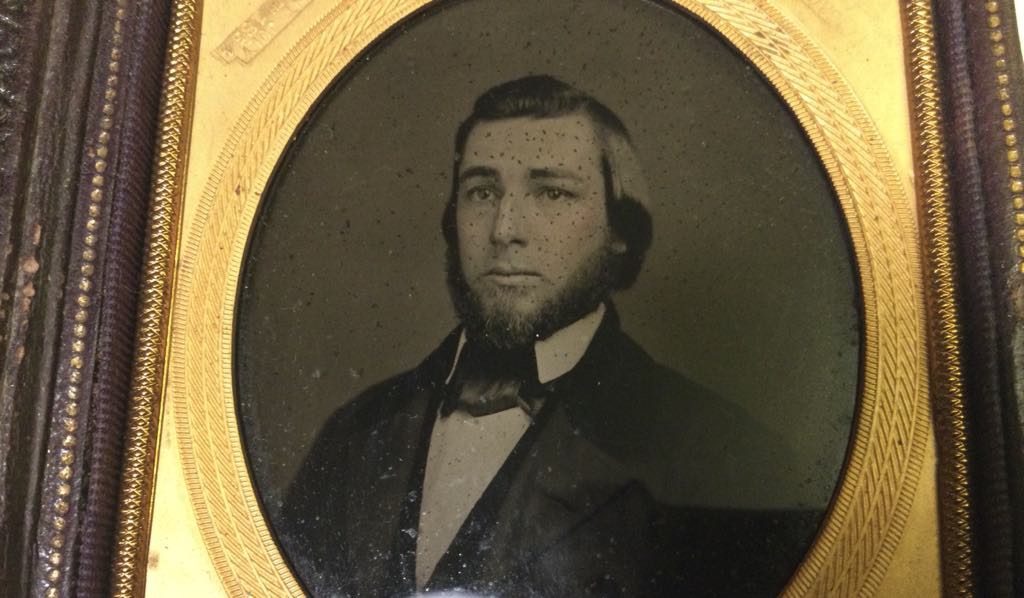

(This photo is undated and unlabeled, but we believe it is Charles Grant. It is the only known photo of him. William Grant tried many businesses to make a livelihood, especially after the war started and the economy was suffering. One business he tried was making photo cases. This is most likely one he made).

In my first blog post about these letters I wrote about John and William visiting Charles in the hospital. This would have been 1861. I’m not sure what Charles had that left him in a weakened state, but I do know he would eventually be released from the hospital. I figured out his age to be about 31 at the time he was in the hospital.

I mentioned part of Charles’s letter to John in an undated letter in my previous post:

“If things do not get better before next winter, there will be a great amount of suffering among the working people,” he wrote in that letter. “The factory where I work is running but two and three days in a week and has been for the past two months and the hands are not making more than $10 or $12 a month and that amount will not go far down here.”

“Thousands who one year thought themselves in good circumstances are now as poor as beggars and who has caused all this but the men who are now the leaders of the Rebel forces and fighting against the best government on the face of the earth. They seem determined if they cannot rule this great nation to the interest of negro slavery to ruin it.”

He ends the letter with a little bit of family business:

“You want to know where Uncle William lives. The last I heard from him he lived in Laraneeburgh, Indiana. I sent you two papers within the last two months. I posted one last night when I got your letter. It had been lying in the office for some time as the new postmaster did not know what part of town I lived in and could not send it to me. This will account for me not answering sooner, but I must bring my letter to a close with sending my love and best respects to you and all the folks.

Farewell,

Charles Grant.”

No one in the family has been able to tell me how John, William, and their mother would find out Charles had been taken captive right before the Battle of Gettysburg, but somehow, they knew.

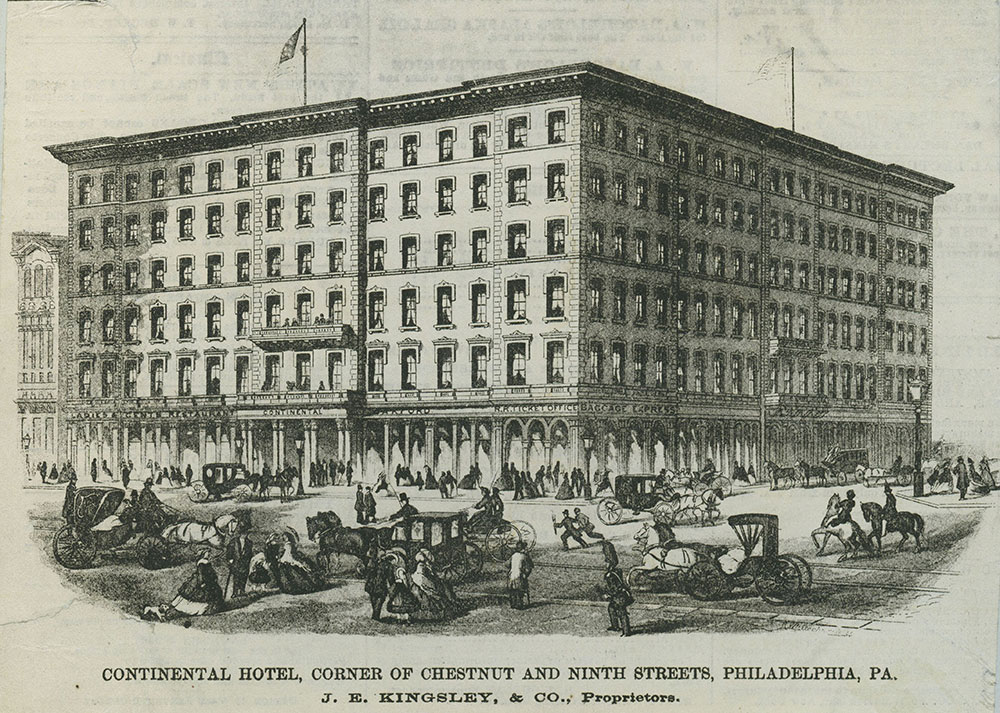

John wrote to William Dec. 22, 1863.

“I have not had a letter from you in a long time so I thought I would write to you and see if you were well and inquire as to how brother Charles is getting along. I have been uneasy for his welfare as our prisoners get very bad treatment at Belle Island and Richmond.”

It was not until 47 years later that William would be told the full story of what happened to his brother and that by the time John wrote that letter, Charles had been dead for at least 18 days.

I’m not sure the full story of how Meville H. Freas of Germantown, Pa. found out that William was looking for more information about Charles. I believe the family story is that it was a letter that William wrote to a newspaper near Germantown toward the end of this life, that clued Melville into the fact William didn’t know what had actually happened to Charles.

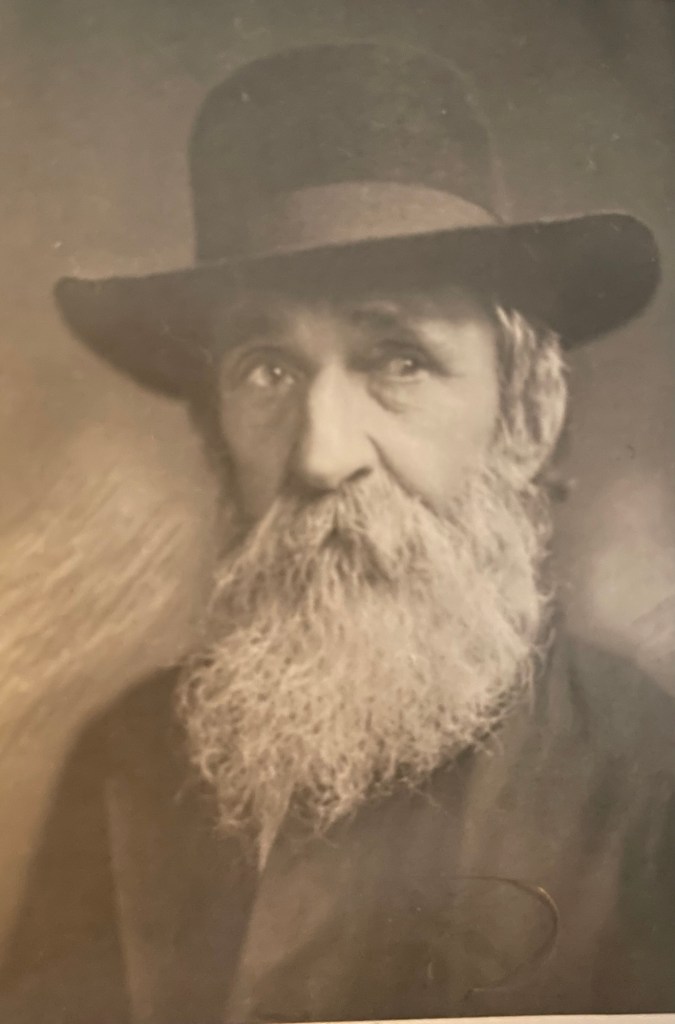

Toward the end of his life, well into his 90s, William was looking for a place to be buried and wrote letters to a couple of newspapers talking about his need for a burial plot. Meanwhile, his family in our little town, was willing to give him a place and wrote him letters to that effect. In the end, he was buried in a cemetery near the veterans home he was living at in Erie, Pennsylvania.

William and Charles had grown up outside of Germantown and stayed in that area for most of their lives.

William would later learn that Charles had enlisted in the Army in Germantown with Melville Freas, Phillip W. Hammer, George Shingle, and Lewis Vogle.

After spending nine months in Libby Prison, Melville Freas was the only one to return home alive.

“January 19, 1910

Comrade Wm. Grant

My dear esteemed friend. A few words about your brother Charles. We were in the same company A of the Bucktails. We fought in the same first days fight in Gettysburg and we were both taken prisoners when leaving Gettysburg as prisoners of war. A Reb Major put us all in line and read to us an order and wanted to parole us, but our government forbid it so we had to go to Richmond and your brother Charles said, ‘I will never live to go back.’

And he did not.

We were put on Belle Isle on July 24, 1863 and I was with him and we both were moved from Bell Isle sick together. We went into Richmond on November 1, 1863 and put in a tobacco warehouse on the (unreadable) floor. No one came to see what ailed us so I said, “Charley, let us lay down and go to sleep and when I awoke in the morning Charley was dead by the side of me.

What he died of I cannot say. I notified the officers in charge and he was taken away and buried and I could not say where, but on the outskirts of the town. Philip W. Hammer was our drum major. He also was captured in the same fight and died at Richmond, Va. I have seen Mrs. Sallie Hammer several times since his death and talked with her concerning him.

Poor Phil — the last time I seen him he had traded his blue uniform for a Reb uniform and a little something to eat. You see we were ‘a starving to death. These men died as prisoners: Charles Grant, Lewis Vogle, George Shingle, and Philip W. Hammer. I was paroled March 21, 1864.”

He also writes about killing someone’s dog and eating it, but that’s not important to our part of the story.

It’s hard to read or understand Melville’s last sentence but further research from a newspaper article our family had and from articles I found online, shows that Melville built a monument in the Ivy Hill Cemetery in Germantown in honor of his friends, including Charles. First, it was a smaller monument and later he had a statue of himself in full Union uniform placed at his future grave. Those articles also stated that Melville was paroled from the Confederate prison in Andersonville, Ga. And that is possible because the prisoners from Libby were moved to Andersonville in February 1864.

Melville had each of the names of his friends who died inscribed on both stones and each Memorial Day he would march in full uniform to the cemetery. One article said he even took his children and later grandchildren with him.

From an article in a Philadelphia paper from May 1917 after listing all the Memorial Day (called Decoration Day back then) events that would be going on:

“And finally, as he has done for many years at 5:00am on this Decoration Day, Melville Freas, Civil War veteran and former private of the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteers went to Ivy Hill Cemetery, loaded his rife with blank cartridges and fired a salute under the statute he had carved of himself which sits atop the grave he will one day rest in.”

As I mentioned above, John had visited Charles in 1861 and he was recovering from something doctors called The Grave (if my aunt transcribed that from the old fashioned hand writing correctly) so I believe he was most likely weakened still in 1863 when we was captured. That’s why he told Melville he would not make it back.

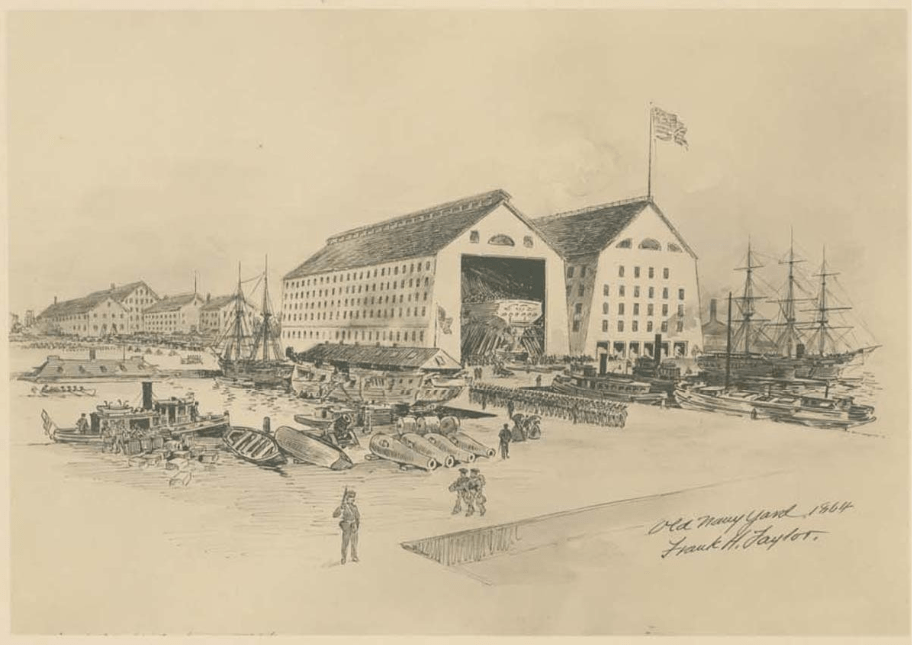

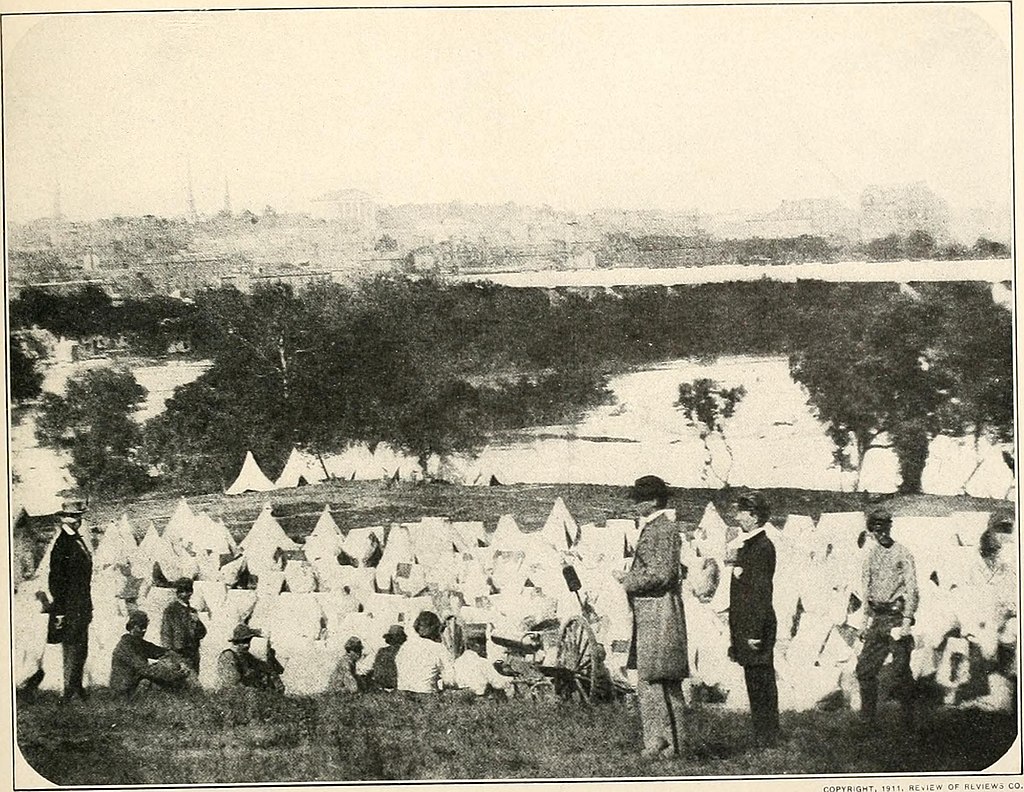

I’ve wondered over the years about what Libby Prison would have been like for Union prisoners of war, and I can tell you, after only a little research, it was not a good place to be held prisoner at or to be a guard at. Belle Isle was just as bad. Illnesses like typhoid and lack of food made conditions miserable for both prisoners and guards.

Libby Prison (left) was a three-story brick warehouse at Cary and Canal Street that was taken over by the Confederate government and became Richmond’s most notorious prison, next to Belle Isle (right).

By 1863, the South was losing, especially after Gettysburg, and because of that, people were starving everywhere.

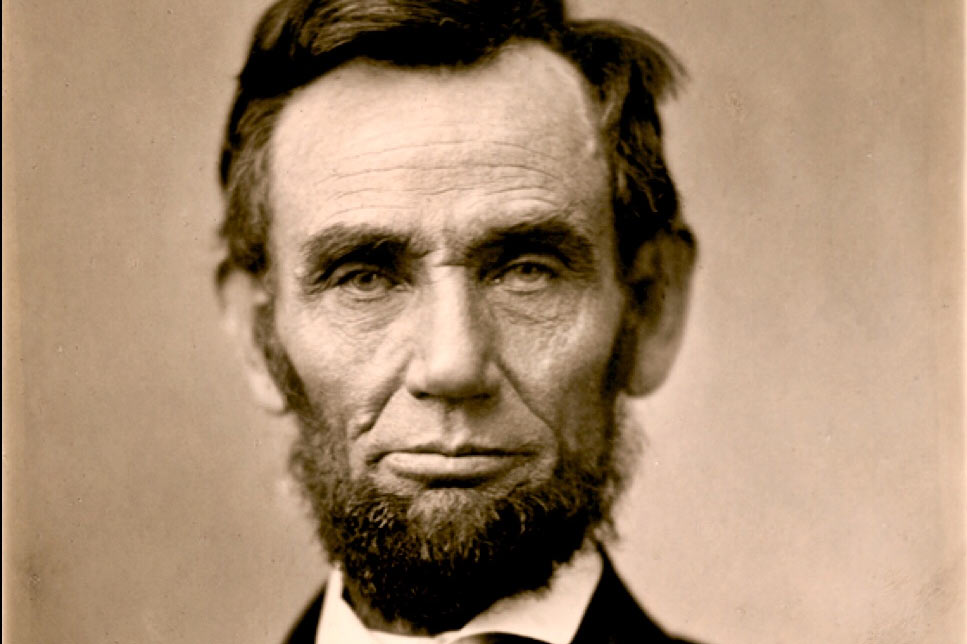

You will recall that in his letter Melville said his government forbade the men from being paroled instead of being taken prisoner. I did some research on this, and it was because once President Abraham Lincoln emancipated the slaves in 1863 it meant that any African Americans, soldiers or otherwise, held by the Southern armies were now free. This infuriated the Confederacy who argued that those African Americans who fought as soldiers for the Union and were captured were runaway slaves and would be sold back into slavery instead of being taken prisoner.

This (rather long…sorry) excerpt from an article on the National Park Service web site under the section of the Fort Pulaski National Monument explains it fully.

“When the Civil War first broke out in 1861, few expected it to last beyond a few months. As the war dragged on, however, realities had to be faced, among them the question of what to do with prisoners of war. Over the first two years of the war, the prisoner of war experience was fairly limited. Most captured soldiers were held for only a few months before being released. One option for release was for the soldier to be paroled—temporarily released on the condition they remain in a certain area and not return to the war effort. Many officers were also exchanged—traded for an opposing prisoner of equal rank and returned to the war.

Everything changed in 1863. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. All enslaved peoples held by states in rebellion were now free. The United States also began the enlistment of African American men into the military. This act enraged the Confederacy who accused the United States of “inciting service insurrection.” As the new United States Colored Troops (USCT) began reaching the front lines, the Confederate Congress issued the Retaliatory Act. This act declared that USCT units would not be treated as soldiers. Instead, Black soldiers would be handed over to state authorities where many would be sold into slavery. The white officers of these units, the act declared, were to be treated as inciting a slave rebellion and “shall, if captured, be put to death.”

With this act, the Confederacy officially refused to treat Black soldiers as combatants when captured. In response, the United States called for a cease of all prisoner exchanges until all soldiers were treated equally as prisoners of war. The Confederacy refused, thus beginning a shift in the prisoner-of-war experience. Suddenly, captured soldiers were being held long-term. Both sides had to create a system of large prison camps to house the thousands of prisoners of war.”

I have a feeling that my family, among many others, felt that had it not been for the Confederacy’s refusal to return their black soldiers, Charles, and many Union and Confederate soldiers, might have come home alive.

One letter from John G. was to, I believe, his stepfather, though I’m not sure since no name is mentioned and addresses what should happen to those many in the Union saw as traitors. It is dated Sept. 6, 1864. John was in Germantown, Pa. at the time.

“I see the convention at Chicago have nominated Gen. McClellan much to the chagrin of the Copperheads who wanted to nominate (unreadable because of the old handwriting) or Gov. Seamor – so you see by the Democrats split and that will proved to be like it was when Lincoln was elected. I have nothing against McClellan, but do not like the platform which the Chicago convention was formed for him to stand on. Upon that platform the Democrats are willing to shake hands with Jeff Davis (that arched traitor) over the graves of our dead comrades who have fallen by his hands and to form a peace with him on almost any terms and more than this yet to take him back to the home of our good old country and pardon him and give him equal rights with ourselves, which should never happen.”

John continued, “Jeff Davis deserves to be hung rather than have our sympathy. Now you will see by this if there is any gentleman about Gen. McClellan or if he cares anything for the thousands of his fellow soldiers who have fallen on every side of him in defense of their beloved country. He certainly will not accept the nomination on such a platform as this, and if he does accept it, on that platform, I am afraid he will never be elected.”

As an aside here, Davis was pardoned in 1868 but McClelland had nothing to do with it because he lost to Abraham Lincoln, who, of course, was assassinated only four months into his second term.

(Abraham Lincoln and Gen. George McClellan)

While researching Melville Freas, I found an article sharing a letter Melville received from a confederate guard at Libby Prison and then Melville’s response. It was an eye-opening letter, adding to the information I’d already learned about Libby Prison and other confederate and Union prisons during that time.

“Melville H. Freas, 248 East Haines street, has received a letter from a former Confederate soldier who stood guard over Mr. Freas when he was a prisoner at Richmond, Va., at the time of the Civil War. The letter was inspired by a newspaper article which Mr. Freas wrote recently protesting against the erection of a monument to Wirz, commandant of Andersonville prison. This article was copied in a Richmond newspaper where it caught the eye of H. C. Chappel, of Amelia Court House, Va., and he wrote as follows to Mr. Frees:

“Dear Old Comrade on the Other Side:

I read a short sketch of yourself in the Richmond Times and learned you had been a prisoner on Belle Isle. No doubt I have looked in your face many a time. The battalion I belonged to guarded there from August 1863 to March 1864.

We had hard times there, as well as the prisoners. We ate the same grub, and had to stand the cold without wood to make a fire, and no chance to get away. But we would go to the iron works and warm up.

I guarded at Libby prison early in 1863. There we got the best grub, and more of it, than any time during the war. The prisoners were all officers, and never gave us any trouble.”

Do you remember the guard, all well dressed in deep blue pants and gray jackets, with gray caps? They composed the Twenty-fifth Battalion. We had got acquainted with many of your boys. It was positively against orders to trade with the prisoners, but we did it all the same; and when we got back to camp those that were caught were called out and sent to the guard house and court martialed.

Don’t you remember that dark rainy night when Colonel Dahlgren reached the river above the island? I happened to be on guard that night. Several of your men asked me what that firing was about, and I told them a war lie. I told them it was over in the city of Richmond and that our battalion was sent to the front and we had to stay on guard.

There didn’t seem to be much sickness in the prison camp, as very few were buried on the island. I remember seeing fifty graves at the hospital. They had only two small tents.

I can truthfully say I never ill-treated any prisoner. No doubt some crank or a mean devil would do it but it was against orders from our officers.

Freas did write the man back, sharing a little more of his journey and he was cordial and thanked him for the letter, but I would imagine it must have been hard for there to be forgiveness after the war. Our nation was split apart — shattered beyond recognition.

It’s split apart in many ways now, but I hope that it will never be so split that it will bring fellow countrymen against fellow countrymen or brothers against brothers.

I know that for some of us, this is already happening, but I pray we learn a lesson from our ancestors about how to lick our wounds, heal our hearts, admit our wrongs, or at least recognize them on both sides of issues, and restore our relationships before it is too late.