Who was Mildred “Millie” Wirt Benson?

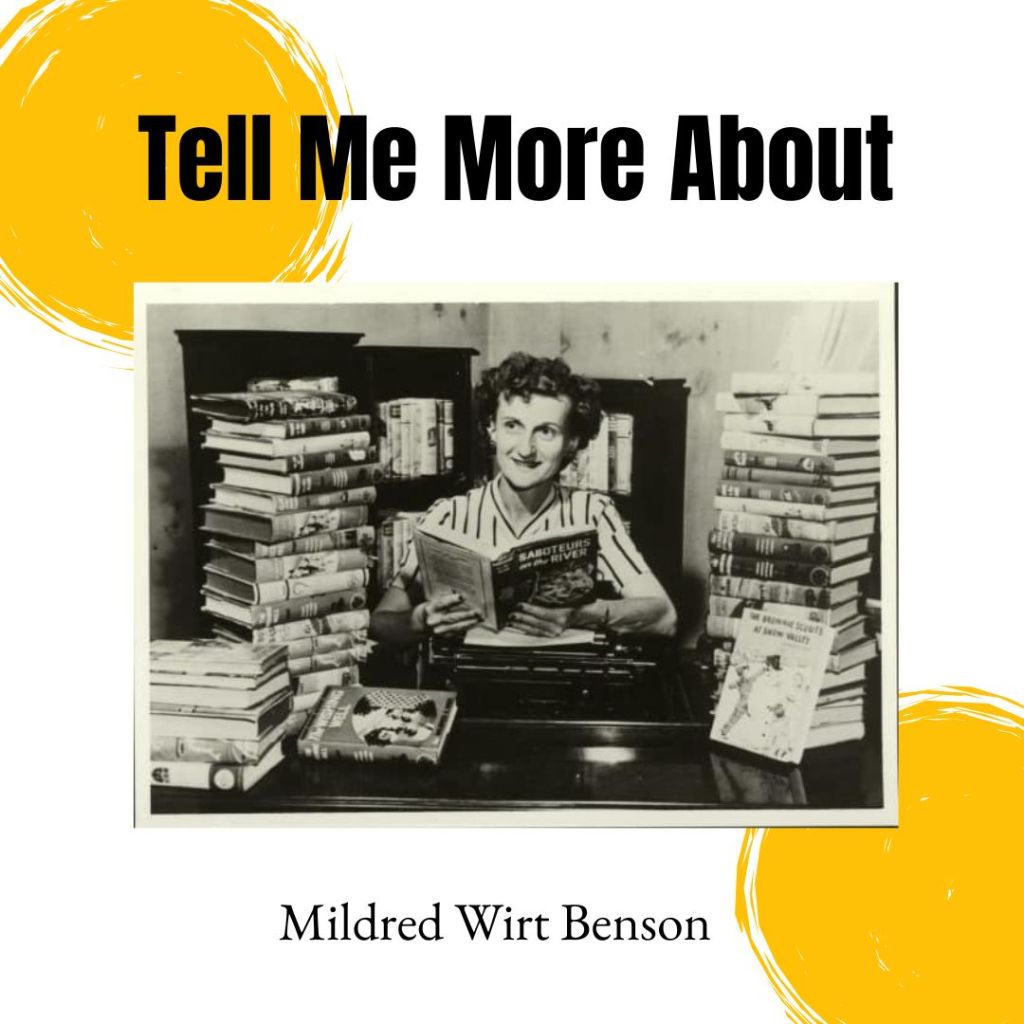

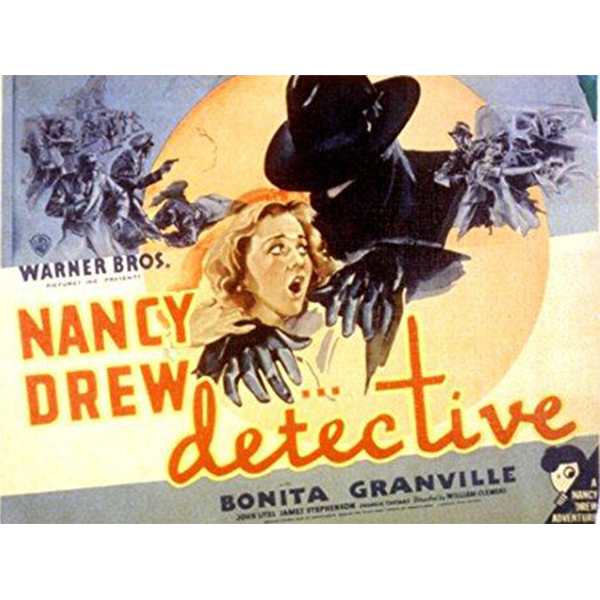

Mildred, or as many called her, Millie, wasn’t an amateur detective, but she was the co-creator of one of the most famous teen amateur sleuths in the United States — Nancy Drew.

For 50 years very few people knew that Millie helped create Nancy Drew.

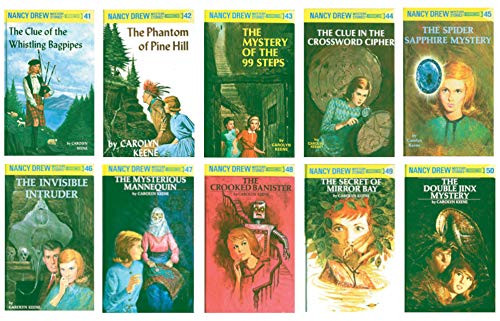

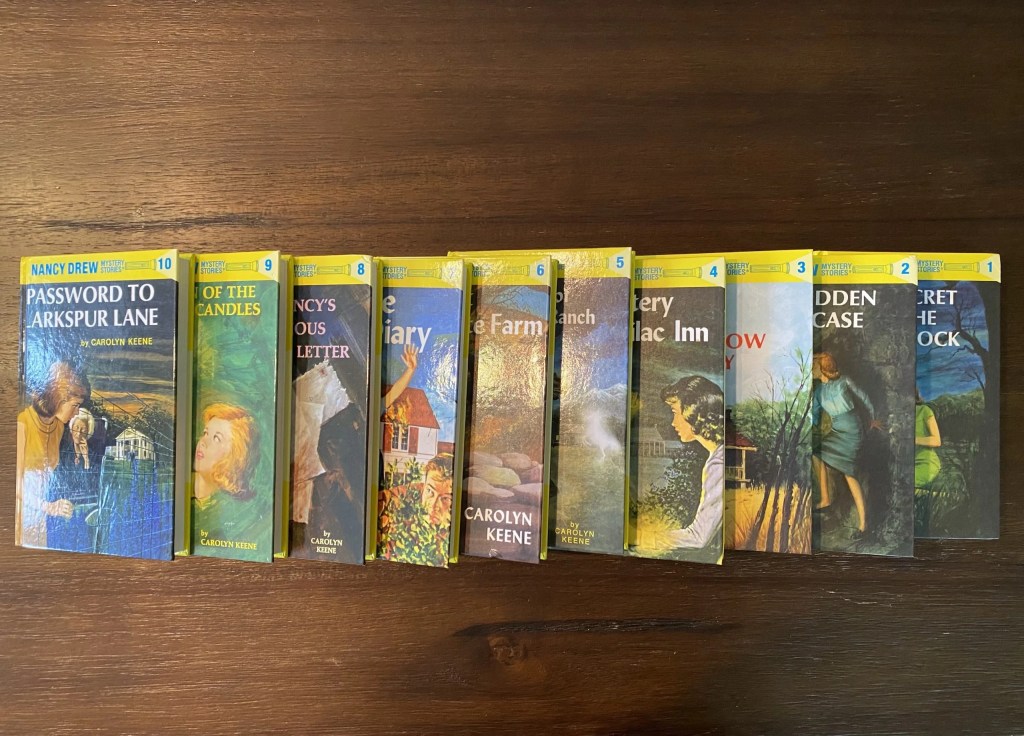

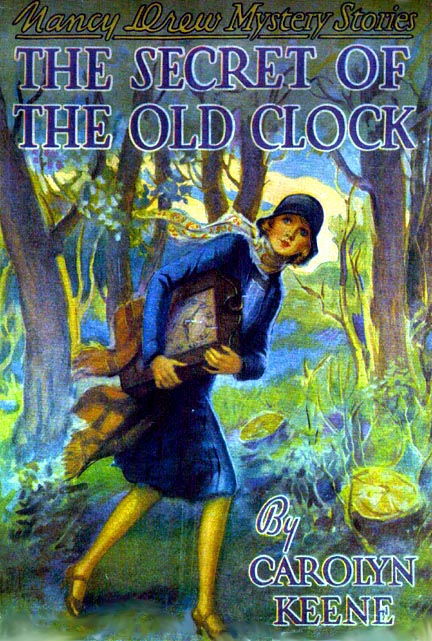

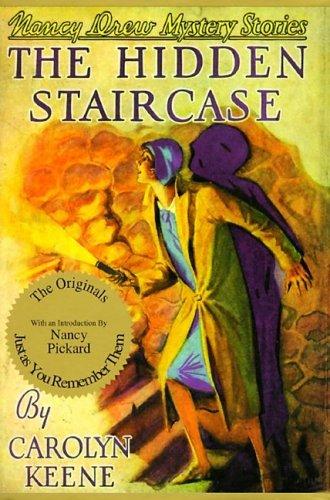

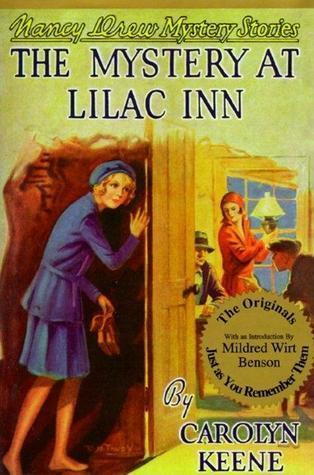

Until 1980, many readers of Nancy Drew didn’t know that Carolyn Keene, the woman listed as the author of the Nancy Drew books, wasn’t actually a real person. She was a pseudonym for some 28 authors, men and women, who create and wrote the stories for the series.

It was a lawsuit between Grosset & Dunlap, the original publisher of the Nancy Drew books and the Stratemeyer Syndicate, the owner/creators of the stories, that brought Millie into the spotlight.

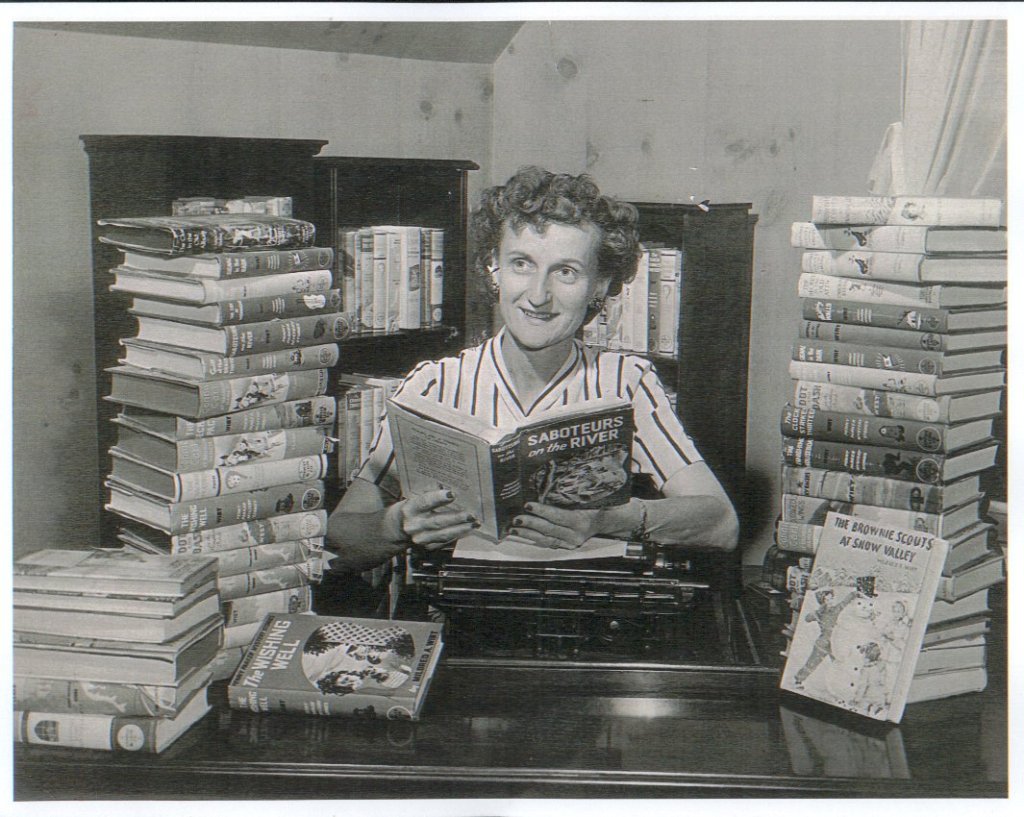

Really, though, Millie had been somewhat in the spotlight before that. She’d written some 130 books in children’s series under her own name from the 30s to the 50s and was an accomplished journalist and world traveler.

What she hadn’t really talked about a lot was her involvement with the Nancy Drew Mystery series.

She’d signed agreements saying she wouldn’t talk about how she’d written 23 of the first 30 Nancy Drew books. She’d written the books with the direction and input of Edward Stratemeyer, founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate and the brains behind many juvenile series, including multi-million selling series like Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, The Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, and Rover Boys.

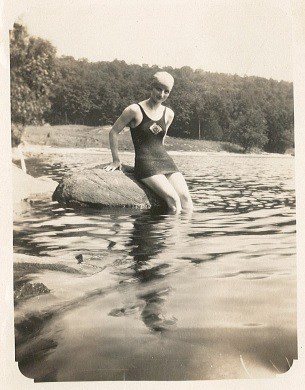

Millie was born Mildred Augustine in 1905 in Iowa, the daughter of a well-known doctor. She wasn’t treated like other girls at the time who were expected to learn how to sew and keep the house.

Instead, Millie was given freedom to explore her own interests and passions. One of those passions was sports. She felt women should have the same opportunities as men to participate and compete in sports she said in an interview with WTGE Public Media in the mid-1990s

“Girls were discouraged from all sorts of athletics,” Millie said. “And I fought that tooth and nail right from the start because I felt that girls should be able to do the same things that boys did.”

While Millie enjoyed sports, such as swimming and diving, she also loved to write, something her mother encouraged her to continue.

Her father, however, said if she wanted to make money, she should do something else and she admits that he was probably right.

She began selling her stories to church papers, but they only paid a few dollars.

She finally sold a story for a whole $2.50.

“That made me a writer,” Millie said in the interview, while laughing. “So, from then on, I was hooked.”

She attended the University of Iowa after school, majoring in journalism and working on the school newspaper. She also worked with George Gallup, the creator of the Gallup Poll.

After graduating, she landed a job at a newspaper, but at the age of 22, she wanted to see what else she could do and traveled to New York City to look for work.

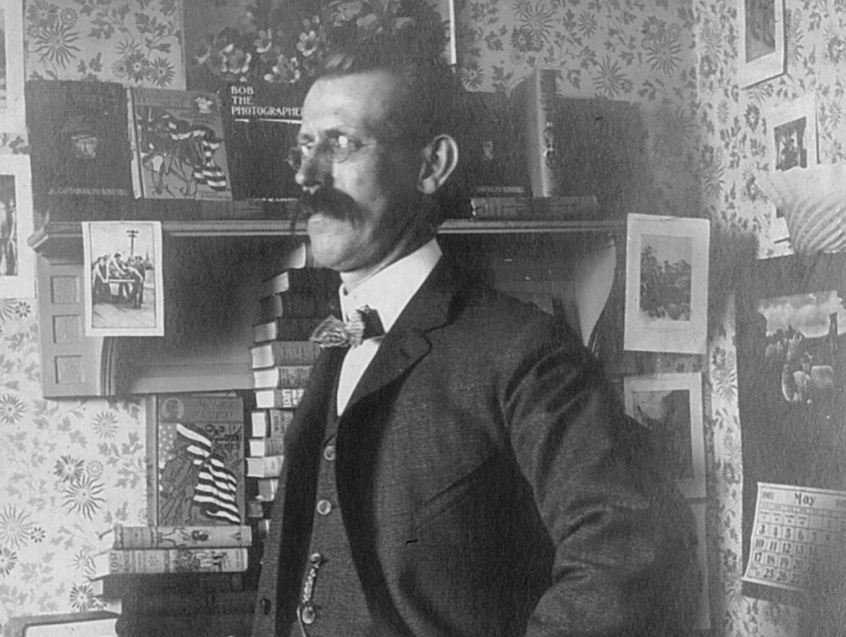

It was there she wrote to Edward Stratemeyer looking for work. Stratemeyer was releasing a book series for juveniles. They were assembly-line type books where he wrote a paragraph detailing what he wanted in the book, including character names and plots. He would send the information he wanted out to writers he knew, and those writers would write the books under the pen name that Stratemeyer controlled and retained the rights to. The writers signed away their rights to credit for the books to Stratemeyer.

While Stratemeyer didn’t have anything for Millie at the time she contacted him, he reached out to her later and asked if she would write a book for the floundering Ruth Fielding series. She did and from there she began to write books for other series for the company. In the midst of all this she also married Asa Wirt in 1928 while attending graduate school.

Millie was reliable, dependable, and a good writer. When Stratemeyer thought about his Hardy Boys series and how young boys liked the boy detectives and then began to wonder if girls would like a girl detective, he turned to Millie.

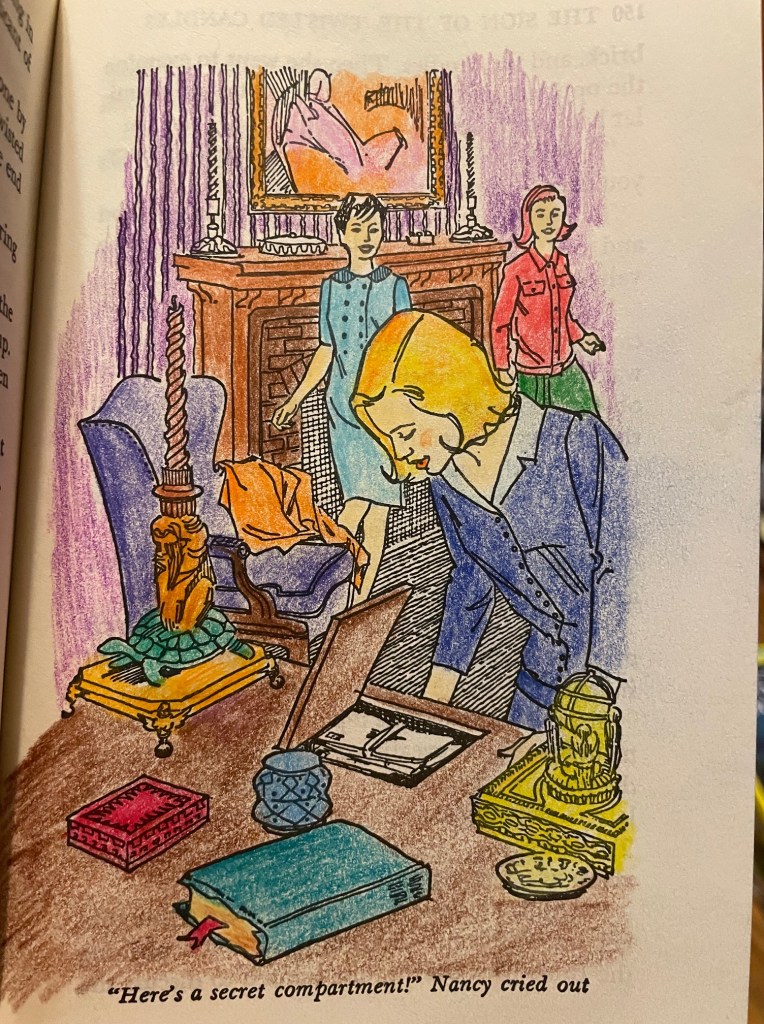

Stratemeyer had the basic idea of Nancy Drew, but many literary historians and Nancy Drew fans say it is Millie who flushed her out and made her who she became. Millie created a version of Nancy that Stratemeyer’s daughter, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, later toned down and changed.

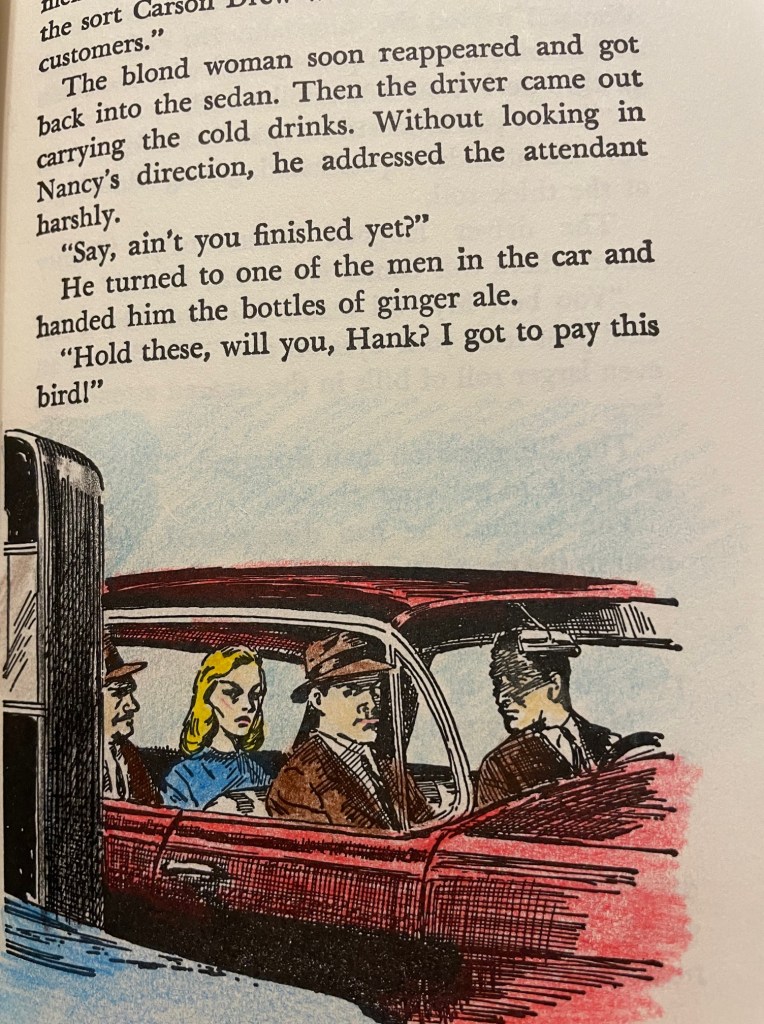

Millie’s version of Nancy was a lot like Millie. She was athletic, adventurous, bold and brash, and never backed down from a challenge. Harriet’s version made her a bit more “perfect” — a rule follower who was polite but still adventurous and who little girls could look up to.

Nancy was what so many girls in the 1930s weren’t allowed to be.

Young girls could live vicariously through her.

Stratemeyer passed away 12 days after the first Nancy Drew book was released. His daughters took over the business after they couldn’t sell it in the difficult economy. Eventually Harriet began taking more control of the Nancy Drew series. Other ghostwriters were working on the series in addition to Millie, who wrote 23 of the first 30 books in the series. In the 1950s Harriet began to rewrite Millie’s original books, changing Nancy’s character, updating some of the material, and, in many ways, stripping away the personality of Nancy that Millie had created.

Millie was working on her own books at that time and had dealt with the illness and death of her first husband and then being a single mother. It was disappointing to see the changes being made but she had other irons in the fire.

In the early 1950s, she was working for the Toledo Times, remarried to the editor of the paper, and being a mother to Margaret Wirt.

She was also writing a character she felt was even more Nancy Drew than Nancy Drew — Penny Parker in the Penny Parker Mysteries.

Penny didn’t see as much success as Nancy, but she didn’t have the mammoth marketing effort that Nancy had, says Millie.

In 1959 Millie was widowed again and afterward she began to live a life a bit more like Nancy Drew — international travel, adventures, independence, learning more about archaeology and even taking flying lessons and eventually earning several flying lessons.

It wasn’t until 1980 when Harriet decided to move the printing of Stratemeyer books from Grosset & Dunlap to Simon and Schuster that more of the public learned about Millie’s role in creating Nancy.

She told WTGE that she could have pushed for her to get credit for the books she’d written. She could have gotten a lawyer and demanded more of the royalties.

She simply didn’t have the desire to put up a fight, though, she said.

“I wrote because I liked to write and I wanted to produce books that girls would enjoy,” Millie said. “And so I didn’t care too much but it got to be … my friends knew I wrote the books and that was sufficient for me. Eventually though it got to be that Mrs. Adams put out publicity to the fact that she was the author and people were reading that.”

One person who was reading all those stories was Millie’s daughter, who asked her own mother if she’d been lying all those years about writing the Nancy Drew books.

Millie hadn’t shared her role in the books with many but when her own daughter started to doubt her, she began to be more open about sharing her role in the creation of the character.

“I thought if my own daughter doubts my integrity, then it’s time I let the truth be known so when people asked me, I stuck my neck out and I told them the truth, which was that I wrote the books.”

Millie was subpoenaed by Grosset & Dunlap during the 1980 when the publisher sued the Stratemeyer Syndicate to keep them from publishing Nancy Drew with anyone else.

They wanted to prove that Harriet Adams didn’t have the right to say who could and could not publish past Nancy Drew books because she had not actually written them. As part of the case, the records that showed Millie had helped developed the series were also subpoenaed.

The truth was finally out there. Millie was the original Carolyn Keene.

Harriet, however, continued to claim she’d written the books right up until her death in 1982 and because the court records were sealed for years, it wasn’t until 1993 when the University of Iowa held a Nancy Drew conference, that Millie really became known as Carolyn Keene.

The conference at the university attracted the attention of literary scholars, collectors, and fans who wanted to know more about the original author and Millie was the main speaker.

Millie, incidentally, was the first woman to earn a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Iowa in 1927.

More fame than Millie imagined hit her after the conference. In some ways, life continued as normal despite the extra attention. She continued to write news and feature stories and her column for the Toledo newspaper. Nancy fans began to contact her, though, asking about her role and for autographs. She was also inducted into the Ohio and then the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame and her typewriter was enshrined at the Smithsonian.

Millie worked first at the Toledo Times, now defunct, and then at the Toledo Blade right up until the day she died, literally. She was writing her column for the paper, at the age of 96, in the Blade office, when she became ill and was taken to the hospital, where she later passed away.

In the article about her death, the Blade wrote about how her writing impacted young girls and women.

“Her books, Nancy Drew buffs have said, allowed teenage girls and young women to imagine that all things might be possible at a time when females struggled mightily for any sense of equality.”

“Millie’s innovation was to write a teenage character who insisted upon being taken seriously and who by asserting her dignity and autonomy made her the equal of any adult. That allowed little girls to dream what they could be like if they had that much power,” said Ilana Nash, a Nancy Drew authority and doctoral student at Bowling Green State University.

The article continues: “Going to work was a way of life for me and I had no other,” she wrote in a December column upon her pending retirement.

In the column, she explained that her legendary work ethic related to being hired by The Times in her third try during World War II.

“I was told after [the war] ended there would be layoffs, and I would be the first one to go. I took the warning seriously and for years I worked with a shadow over my head, never knowing when the last week would come,” she wrote.

Millie’s column was called, “On the Go With Millie Benson.”

Millie was described in the article about her death as fiercely independent and “always willing to go after a story she was assigned or had set her sights on.”

She almost never took a day off. In fact, the day after she was diagnosed with lung cancer in June, 1997, she was back at her desk working on her next column saying her desk was where she needed to be.

Millie once said in an interview that she never looked back on the books she’d written, “Because the minute I do I’m going into the past, and I never dwell on the past. I think about what I’m doing today and what I’m going to do tomorrow.”

I have had the opportunity to read a couple of books written by Millie, before Harriet got to them, and I have to say I did enjoy them. I didn’t know at the time that other books had been revised, and I had an original copy of Millie’s work, but when I found out, I could see the difference between Millie’s writing and other ghost writers/Harriet.

I am going to be purchasing a couple of books from Millie’s Penny Parker series to see what that series was like as well.

As president of the Nancy Drew Fan Club, Jennifer Fisher is considered a Nancy Drew and Mildred Benson expert. She operates the website nancydrewsleuth.com and donated her Nancy Drew collection several years ago to the Toledo library and now curates items to be added to the collection.

She is currently looking for information on Millie, from letters to manuscripts, to any memorabilia of hers that someone might have.

On her site Jennifer details the life of Millie and talks about the impact her books (130 of them all together, including the Nancy Drew books) made for young women.

She also has a list of all of Millie’s books by series: https://www.nancydrewsleuth.com/mwbworks.html

Jennifer wrote about Millie in a special section on the site, including detailing the trial where Millie spoke about the conflict that eventually arose between her and Harriet Adams.

“On the stand when shown letters between herself and Harriet regarding criticisms and difficulties, she recalled that this was “a beginning conflict in what is Nancy. My Nancy would not be Mrs. Adams’ Nancy. Mrs. Adams was an entirely different person; she was more cultured and more refined. I was probably a rough and tumble newspaper person who had to earn a living, and I was out in the world. That was my type of Nancy.”

And it is that type of Nancy, and that type of woman, who so many women over the years have been drawn to despite the changes. Even with the changes later made to the books, the heart of Nancy, created by Millie, always remained.

Additional resources:

Mildred Wirt Benson works: https://www.nancydrewsleuth.com/mwbworks.html

Mildred Wirt Benson biography on Nancy Drew Sleuth: https://www.nancydrewsleuth.com/mildredwirtbenson.html

Nancy Drew Ghostwriter and Journalist Mildred Wirt Benson Flew Airplanes, Explored Jungles, and Wrote Hundreds of Children Books: https://slate.com/culture/2015/07/nancy-drew-ghostwriter-and-journalist-mildred-wirt-benson-flew-airplanes-explored-jungles-and-wrote-hundreds-of-children-s-books.html

Millie Benson’s Fascinating Story, Author of the Nancy Drew Mysteries | Toledo Stories | Full Film https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIs5sRWzEV8

Information on Millie from the University of Iowa: https://www.lib.uiowa.edu/iwa/Millie/