I pulled into the driveway of a little house that looked as if it had been lifted out of Northern Ireland and dropped, unscathed, into the hills of Pennsylvania. The ceilings were low, the windows were small and cute and the stone fireplace had been built by hand.

On one side of the house was a cow pasture and on the other a tiny, century-old cemetery with a sign on the metal gate that read “Enter At Your Own Risk.”

I blew my nose as I parked and began to rehearse what I would say to the elderly Irishman inside, determined to not let him talk me into staying for tea. I did not want tea. I wanted to go home, lay down and fall asleep after a long day of work at the local weekly newspaper and catching a cold that had only gotten worse as the day went on.

I would simply tell Rev. Charles Reynolds, the aforementioned Irishman, that I was too ill to come in, but would stop again another day when I was feeling better.

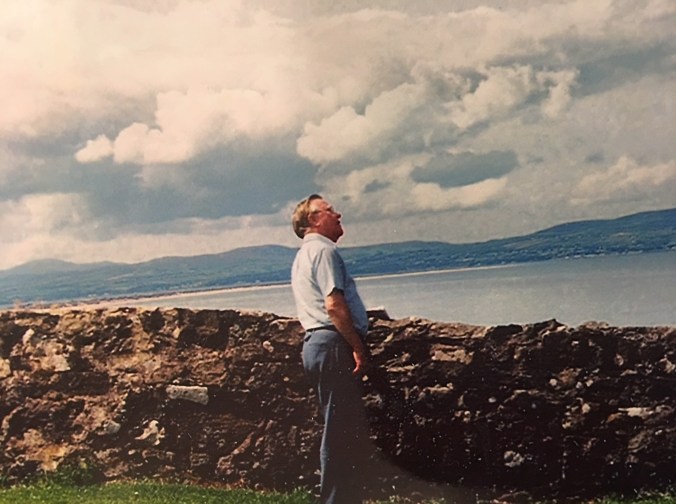

The door swung open and a man with blond-white hair, glasses slipping down his nose, stood there in a button up dress shirt and a pair of dress pants, his traditional garb for as long as I had known him; as if he had just returned from church.

“Hello, Rev. Reynolds, I’m sorry I can’t stay long, but I seem to have a cold and I don’t want to get you and Maud sick,” I steeled my resolve to not be swayed by his Celtic charm.

“Come, come. Have a cup of tea,” his Irish brogue was thick. “Maude, put the kettle on. We’ll have some tea and Lisa will feel better.”

“But I -”

“Come. Come.”

He was already walking away from me, gesturing for me to close the door.

Maude, his gray-haired wife, had dutifully shuffled into the kitchen, off to the left of the front door, and placed the kettle on the stove.

“Yes, Paddy.” She nodded curtly at her husband, like a soldier to a superior.

Her tone hovered somewhere between affection and sarcasm.

I sat at the kitchen table and waited for the whistle of the kettle as cookies, crackers, plates, tea cups, a bowl of sugar cubes and cream was placed on the table before me. water was poured into a teapot filled with loose tea and steam rose as it was poured into my cup and bits of the leaves settled at the bottom.

Rev. Reynolds leaned over the table and added a cube of sugar to my cup. Two, round white horse pills pills showed up next.

“There now. That will be just what you need. Tea and vitamin c.”

Rev. Reynolds’ had a doctorate but sometimes he seemed to forget it was in theology.

The dainty tea cup covered in blue patterns was warm in my hand and clinked against the plate when I set it down. Being served tea this way was a far cry from tea at my house, served in a mug with a tea bag after pulling it from the microwave.

“So, have you talked to Ian lately?”

I marveled at how Rev. Reynolds had the worst timing and the least tact of almost anyone I knew, other than my former editor.

I had no interest in talking about my former editor. My departure from the daily newspaper I had once worked at hadn’t been pleasant.

But if it hadn’t been for that job, my first in newspapers, I wouldn’t have met Rev. Reynolds.

********

“Hey, Lisa – this is Rev. Reynolds.”

Ian was the editor of the local daily I had started working at while still in college. He had a slight nasal tone when he spoke, like he had a permanent stuffed nose.

“He’s from Northern Ireland and would be a great source for a story about all the drama going on over there. We can localize an AP story. Interview him and give me 15 inches for the front page tomorrow.”

Localizing, or “adding local color” to a national or international story, was a favorite pass time of Ian, or as Rev. Reynolds would often call him “eeeeeahn”. The concept of localizing involved using an interview or information from a local resident and adding it to a story we had pulled off the Associated Press wire. Ian wanted me to add Rev. Reynolds’ comments to a story about the possible peace deal being negotiated between the Irish Republican Army and the United Kingdom.

“Oh, you’re Irish! Do you speak Gaelic?”

The elderly man with a slightly bulbous nose and holding a stack of papers, looked indignant.

“Noooo!” he cried in a drawn-out Irish accent. “That is the language of the rebels!”

I had no idea who “the rebels” were. Had we just switched to talking Star Wars? I didn’t know, but for the basis of needing to write a story for the next day’s paper, I needed to know.

Even after we talked I was a bewildered by it all. to this day I remain bewildered. It wasn’t until later I started to connect that rebels appeared to be synonymous with “Catholics.” In the world of Rev. Reynolds. As a Protestant, Rev. Reynolds had been raised in a family who supported Northern Ireland remaining within the United Kingdom. Most of those who supported the province remaining within Great Britain were protestant and those who wanted to break off and be part of the Republic of Ireland were Catholics. That’s about all I can explain because even after he explained it to me, wrote a book about it and told me to read it, and I looked it up online, I still can’t wrap my head around why there is an Ireland and a Northern Ireland.

In some sort of ironic twist straight out of a Hollywood script, Rev. Reynolds ended up in the hospital at one point after our friendship grew and his roommate was a local priest, who was well known to my husband and I. Not only did a friendship develop between the two but through him Rev. Reynolds developed a friendship with an Indian priest who was serving as an assistant priest at our local Catholic Church. I remember Rev. Reynolds inviting my family, including my parents, and the local priests to dinner at a local restaurant where he spoke about his life coming full circle – from a distrust of Catholics at a young age to an affection for members of the church he had come to call friends.

From that day at the paper, I became the contact for Rev. Reynolds for his various projects. And he always had a project underway. A fundraiser for an Indian village damaged by a tsunami; a new book he was writing and wanted publicity on; a need to bring awareness to the need for more women in the medical field in India. They were all worthy causes but sometimes it was hard to keep up with his ever-growing list of charitable pursuits.

********

“Tea has healing properties,” Rev. Reynolds slipped another cube of sugar into my tea.

“Tea has healing properties,” Rev. Reynolds slipped another cube of sugar into my tea.

The tea came from a 50-year old stash in the shed across the dirt road that they’d brought back from India during their time as missionaries. Rev. Reynolds pulled back a tarp one time to show me the small, square white and green boxes stacked high, each full of traditional, loose leaf Indian tea. They’d had it shipped to them from India and knowing Rev. Reynolds he’d found a way to get it there at little to no cost to him. Rev. Reynolds had a way of convincing people they wanted to help him.

I began to realize my headache and body chills were fading. Maybe Rev. Reynolds was right about the healing properties of tea after all.

It was often hard for me to imagine this man, sitting across from me at the table, now in his mid-70s, as a young man living in Northern Ireland. During World War II he joined the Royal Air Force and was stationed in India, where he fell in love with the Indian people, but also with a young woman from a little farming village in Pennsylvania who was in the country as a missionary. After the war he and Maud became missionaries to the country for 20 years. Maud had been an only child who had grown up on a farm and had been taught how to do anything a man could do – including fixing cars and hiking through some of the most remote areas of the world.

Over the years they met many famous people, including Mother Theresa, the Dalai Lama and several American and British political leaders. Rev. Reynolds also once lead the leader of Northern Ireland around the United States in a public relations campaign in support for Great Britain continuing it’s rule over Northern Ireland. In 1995 he was also appointed as an OBE (Order of the British Empire) by Queen Elizabeth II.

But to me he was simply the man who called me to help him send an email, figure out why his computer wasn’t working, write a news story, or eat a traditional Irish meal of boiled ham, potatoes, carrots, turnips and cabbage with him and his wife, or sometimes some new person he had taken under his wing. In truth, we were almost family, since Maud was related to my grandfather’s family, but we were also family because we somehow adopted each other.

*****

The day before our wedding my strong-willed great aunt and the maybe slightly more strong-willed Rev. Reynolds battled over where the main flower arrangement would be placed for the ceremony.

“The arrangement will go on the altar because it deserves to be the center of the ceremony,” Aunt Peggy said in her thick Southern accent.

She had designed all the flower arrangements, full of gorgeous purple lilies. She transported them to Pennsylvania from Cary, North Carolina, stopping several times along the way to spritz them with water and make sure they stayed cool. Once she arrived at the century old house I had grown up in, she rushed them into the cool stone basement.

On rehearsal day she placed a large, expansive arrangement on the altar between the unity candles and stepped back to inspect her handiwork.

We all stepped back.

We all admired its beauty.

All except Rev. Reynolds.

Rev. Reynolds picked it up and moved it to a stand that was sitting off to one side of the altar.

“It can not be on the altar. The altar is for the candles and the holy book.”

“It will be fine in the center of the table.”

“Noooo….you can no’ place it there.”

The more agitated they became, the thicker their respective accents became.

The exchange went on for several moments longer with the flowers being moved back and forth as each person explained their position.

It was like a scene from a sitcom.

The rest of us wished we had a bowl of popcorn for the show.

I thought my aunt’s eyebrow, which arched when she was indignant, was going to fly right off her face. Her lips, pursed tight to keep herself from saying something “unpleasant”, were now a thin red line.

Rev. Reynold’s ears and nose were glowing red.

Eventually, a compromise was reached and the arrangement was placed to one side of the altar, still in an appropriately visible location, but not in a place that would detract from “the holiness of the altar.”

Rev. Reynolds could be bull-headed, sometimes even rude, but those moments were overshadowed by a deep desire to serve, to be the hands and feet of God. No matter where he was, from the green hills of Northern Ireland to the remote forests of India, to the tiny Pennsylvania farming community, he never shied away from sharing the gospel. In the last book he wrote, “He Leadeth Me,” he wrote about meeting with the Dalai Lama with a contingent of missionaries and leaders from the United Methodist Church. They hoped to help the exiled Tibetan leader and his people, who had been pushed from their country.

The Dalai Lama turned abruptly to Rev. Reynolds during one conversation and asked, in English, “Why do you help my people? We are not of your faith or your culture, yet you help us.”

Rev. Reynolds said he wasn’t sure how to respond at first, surprised by the question, but believes the Holy Spirit directed his words when eventually relayed Luke 10:33.

“I repeated the simple story of the Good Samaritan and the teaching of our Lord Jesus that we are to love our neighbor, even though that person was not of our faith, our race or our culture. Anyone in need of help and who could not help himself was to be touched by the grace and love of our Lord. This discussion continued on into our knowledge and kinship with God.”

I have many regrets in my life and one of them is driving by the hospital that day, ignoring Mom’s warning that it might be my last chance to say my goodbyes. I was in denial that death could ever come for someone so full of life. A few days later I stood in the back of the church the day of the funeral and held my crying baby, mourning loss and celebrating new life simultaneously.

There are many times since I have felt the void of the insistent Irishman who often drove me to my wits end, blessed me with his kindness, and demonstrated to me what it means to truly live in the footsteps of Christ.

*******

“I believe God made us all as individuals, each with their own life’s work, calling and talents. We should therefore find a place of service in this gigantic jigsaw puzzle that we see as the world, and as having found it, we should serve to the best of our ability. Shakespeare understood this when he had Polonius say ‘This above all to thine own self be true.; However, we know that Polonius was not true to that affirmation, so Shakespeare added a contra when he wrote, ‘All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.’ True, many people wear masks and act a role, but nobility of spirit requires identifiable personal characteristics.”

~ Rev. Charles Reynolds

“I’m hungry.”

“I’m hungry.” Then I tiptoed into my son’s room, where he had already fallen asleep, and kissed his head. Suddenly, in that darkened room, a sliver of light from the street leaking in, he wasn’t 11 anymore in my eyes. He was still five and innocent and little and all I wanted to do was scoop him up and hold him against me.

Then I tiptoed into my son’s room, where he had already fallen asleep, and kissed his head. Suddenly, in that darkened room, a sliver of light from the street leaking in, he wasn’t 11 anymore in my eyes. He was still five and innocent and little and all I wanted to do was scoop him up and hold him against me.